Music, part 2

In part one, I explored how a CDJ turns a CD player into an instrument—something you play with, not just play from. But the physical device is only half the story. The other half is software, and it reveals something fundamental about attention.

Why does a CD player need ethernet and USB audio? The answer is Rekordbox — and understanding it might reveal what’s been missing from how we interact with music.

I thought I’d kept up with music player software: early sampling on my Dragon 32 (32K doesn’t get you far), trackers in the 16-bit era, Winamp, Soundjam, iTunes, Zune, Spotify. I’d even designed music products around some of them.

But this was new to me.

Timecode and trax

Rekordbox. I’d never heard of it.

Not actually new — it has a history. Mixvibes and Looptrax were sample-playing apps in the 90s. Looptrax was somewhat Ableton Live-ish. Mixvibes became a digital vinyl system — I don’t recall it, but another, Stanton Final Scratch I do remember.

Records with timecode controlling digital playback. Looked cool, though I never used it. Pioneer DJ tapped Mixvibes in 2008 to build a digital media tool for their hardware. They called it Rekordbox.

Beyond the library

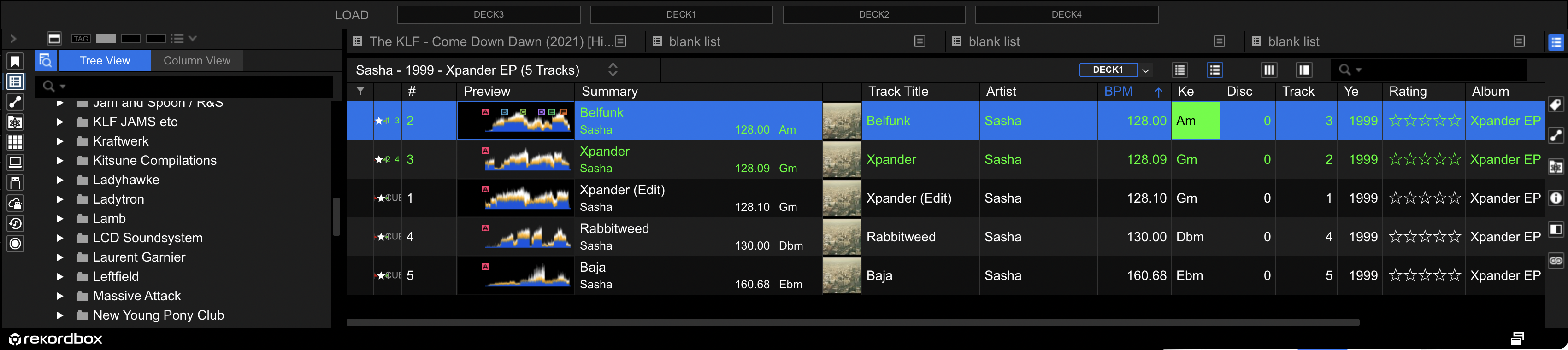

If you’re building USB playback into CD players, you need music library management. At first glance, Rekordbox looks like other music libraries—the spreadsheet view of titles, artists, metadata:

But it’s also a playback engine, representing all the tools that physical decks and a mixer provide—digitally.

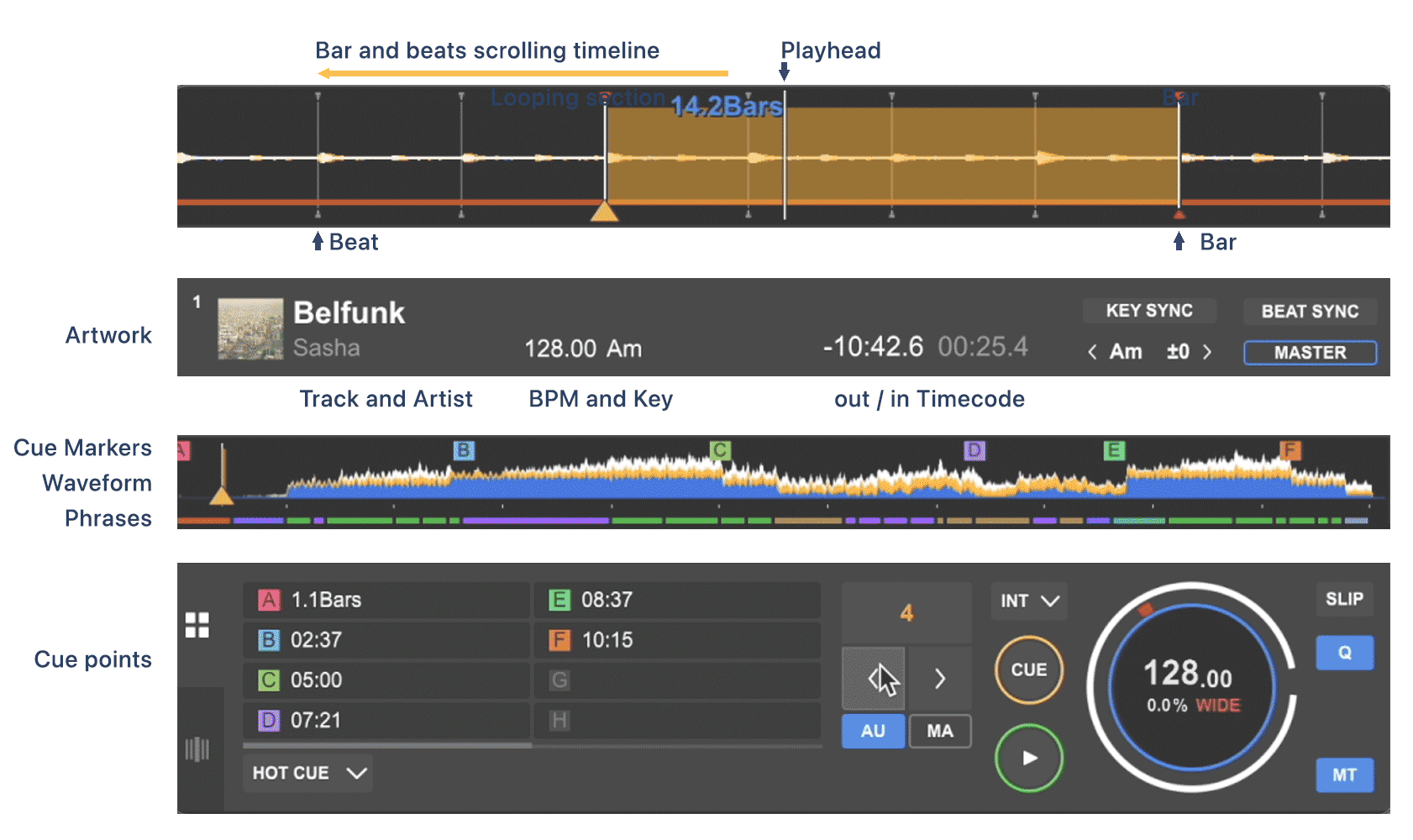

Standard stuff: playback controls, progress bar, time/pitch stretching, looping. Playing one track looks like this:

But this is where it gets interesting.

User interface for now

You can run 2 or 4 decks simultaneously. Instead of a simple progress bar, each deck displays:

- A large waveform moving past a static playhead

- A “spinning” virtual disc with playhead position

- Position markers along the track

- All visible at once, in one place

Plus volume and EQ for each track. It’s an overwhelming amount of visual information representing music. Let’s break down what you’re actually seeing:

Multiple views of now

The display shows multiple representations simultaneously:

- Bar and beats scrolling timeline - rhythmic structure

- Waveform - frequencies and volumes

- Position - where you are in the song

- Phrases - sections and movements

- Cue points - markers you’ve set

This isn’t decoration. Each layer serves a specific cognitive function.

Here’s what’s crucial: the focus of attention is the now — the playhead. Everything else moves past it. The scrolling beats and waveform represent what’s coming, what’s happening, what’s just passed.

With a second track lined up, you’re looking ahead a few bars. You’re matching beats. You’re anticipating transitions. You’re listening to two tracks at once, hearing where they’ll align. Once that’s complete, line up the next one, and think about the one after that.

This is active listening as a flow state.

The difference is more

Compare this to Spotify, iTunes, or any streaming interface. You get:

- A static progress bar

- Track information

- Play/pause/skip controls

You can listen, but the interface doesn’t give you anything to do with the music. It’s consumption, not engagement.

Rekordbox (and DJ software generally) creates an interface where you’re constantly making micro-decisions:

- Where to set cue points

- When to trigger loops

- How to blend frequencies

- When to transition

- What to play next

The structure of flow

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi identified the conditions for flow states:

- Clear goals

- Immediate feedback

- Balance between challenge and skill

- Loss of self-consciousness

- Sense of control

- Altered time perception

DJing hits every one. The goal is clear (keep people dancing, or maintain energy, or create a journey). Feedback is immediate (you hear it, you see the waveforms, you feel the crowd). The challenge scales with skill. You’re too focused to be self-conscious. You control the music’s flow. Time disappears.

The hypothesis

DJing creates a flow state of active listening.

Not just for the DJ, but potentially for the listener if given the right interface. What if we could design music playback that maintains some of this architecture of attention, without requiring the full skill of DJing?

What if we could make listening active again?

That’s the question that led me here, and the one I’m still exploring.

continues…