Music, part 1

I’ve taken a break from the usual to scratch a design itch regarding music players, and how we interact with it can induce a flow-state.

The passive listener

We love music. Most of us love listening to it, at least. But somewhere along the way, listening became background radiation. Music plays while we work, commute, exercise, cook. It’s there, but are we really there with it?

When COVID hit, I got into making music. Making music forces you to listen differently — actively, critically, structurally. You hear the parts, not just the whole. It’s quite full on, and you can lose hours.

But playing music back? That’s remained passive for most of us. Maybe you used to make mixtapes, now playlists.

What if listening to music wasn’t passive? What if being more engaged with the sequencing of what’s playing was enough to snap into that state? The hypothesis I want to sketch out, is that DJing creates a flow state of active listening — and not just for the DJ. Something in the interface itself creates a fundamentally different relationship with music.

But first, a little bit of history and unboxing…

From physical to digital

The shift from physical to digital music was about convenience. CDs were great — I never fully got into vinyl. So big, fragile and heavy! Although once you accumulate enough CDs you learn they’re also big and heavy.

When digital files appeared in the 90s, it was literally a weight off my shoulders. I kept buying CDs for years, but being able to move music around freely was a joy.

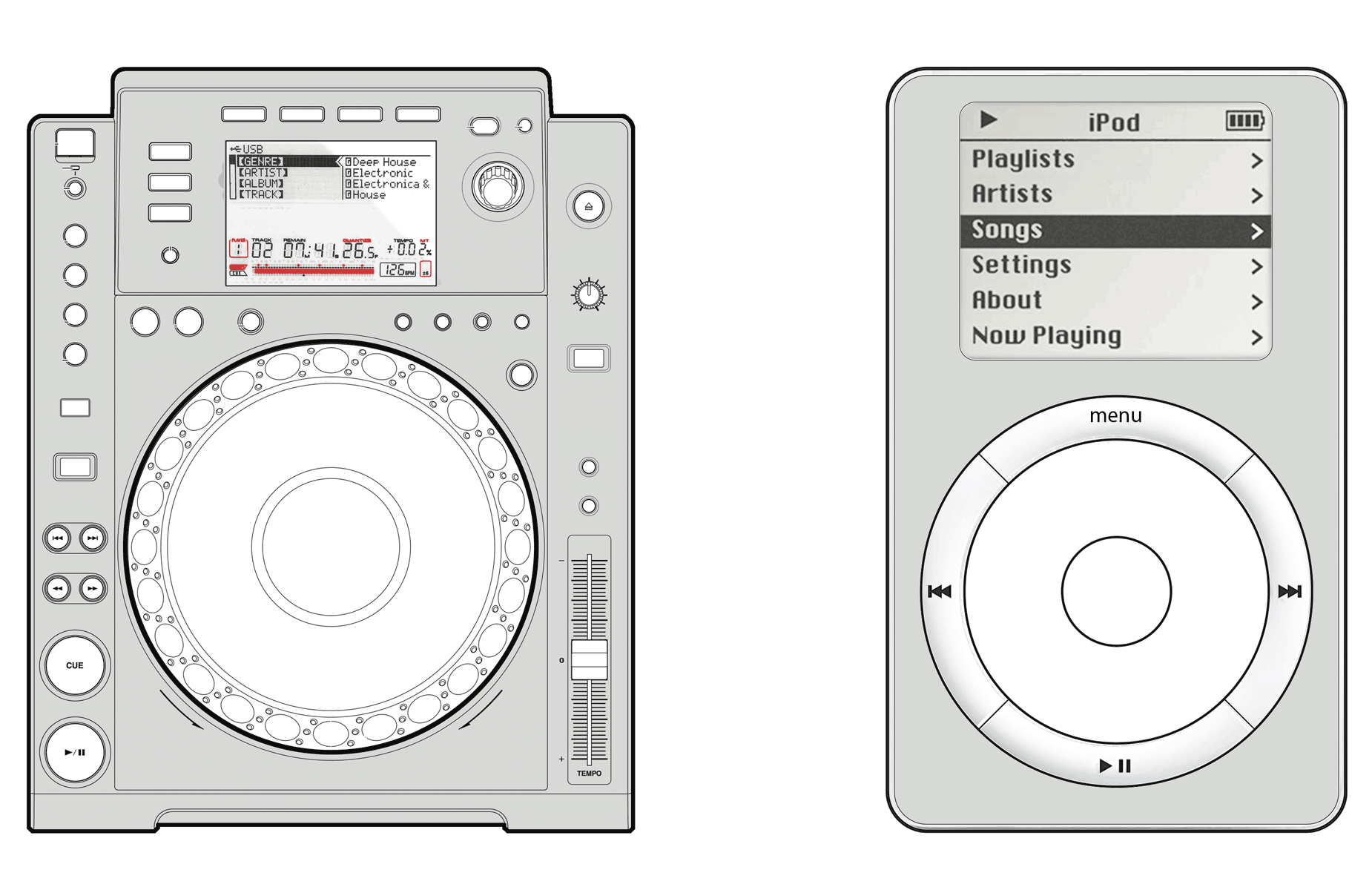

Innovation was rapid: MOD trackers in the 16-bit era, then Winamp, Soundjam and iTunes leaping forward, and back to hardware: the iPod and iPhone trace their lineage directly. (Straight Dope on the IPod’s Birth

The cost of convenience

iTunes tried to make buying easier than piracy, but DRM squeezed users into specific platforms. As Steve Jobs made clear, this was the demand of record labels, not platforms or artists.

Then streaming arrived. Links replaced files. Ownership evaporated. An infinite pool of music — mostly for the good, I think, but something was lost. Not just ownership, but the relationship to your collection. The tending of files. The intentionality of choosing what to keep.

We gained infinite access. We lost focused attention.

A parallel path

Meanwhile, a different story was unfolding. Less visible but equally innovative: the CDJ, developed and refined as a tool for DJs to play digital music.

30 years of the CDJ: the technology that revolutionised DJ culture, DJ Mag

This was a completely separate timeline for me, one I’m only now discovering. And I think it’s the key to understanding what’s been missing.

Hello again CDs

I reorganized my house recently and rediscovered all my CDs—caseless, but clean, stored in those big 100x zippered albums. But could I find a working CD player? Apart from a gaming console, no.

A good CD player should be affordable now, right? Wrong. Few companies manufacture them, certainly not reputable brands at competitive prices. eBay had options, but not many in good condition. Rubber bands and other parts wear out.

(My dad needed a CD player at the same time. He got a Cambridge Audio unit — good, but over £300.)

What if CDs, but more fun?

I prefer things with multiple functions. When a friend mentioned little Tascam CD players that can change pitch, tempo and EQ for learning guitar or vocals—wow. https://tascam.jp/int/product/cd-vt2/top

Quite niche, and hard to find. But I remembered CDJs from the 90s—they should offer similar features, and they’re more widely available.

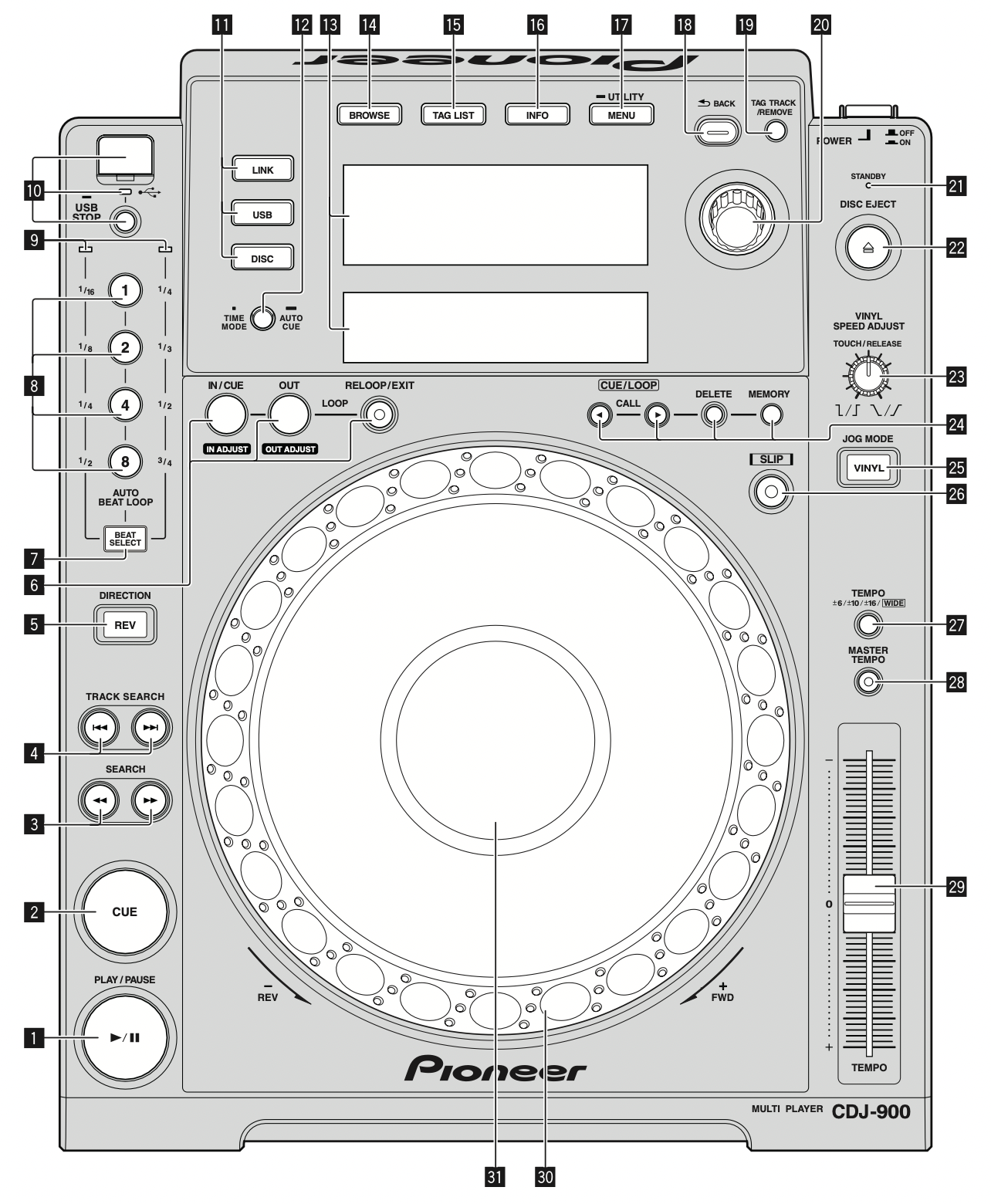

eBay rewards patience. One bargain CDJ-900 later, I can play CDs again. But more importantly, I can play with them.

What is old is new

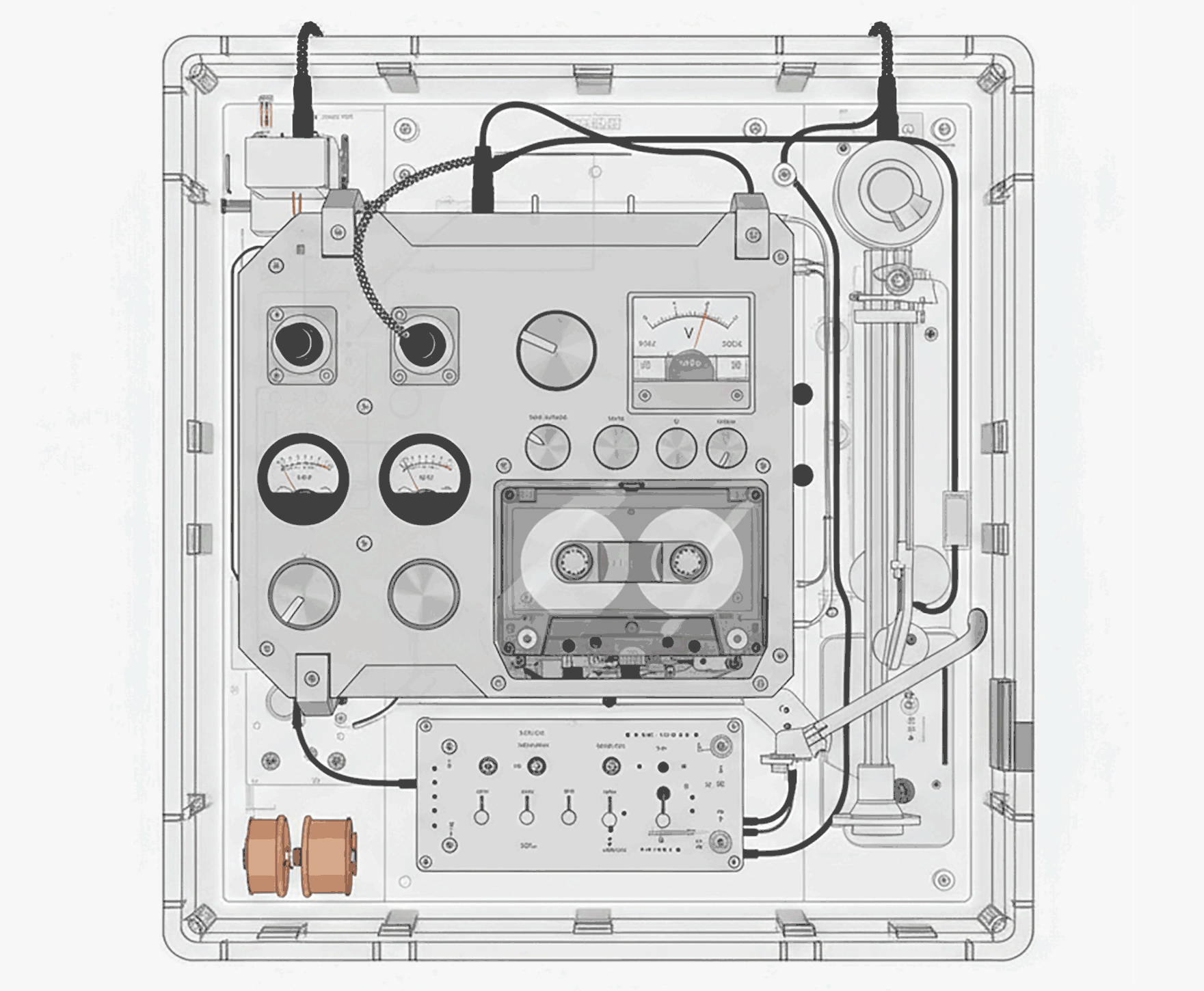

Play with… yeah, interesting. Now, this is a 16-year-old CD player for a very specific use case. It does things I hadn’t realized it would do, and I’m going to describe them from a complete newbie perspective — because what struck me wasn’t just what it does, but why these features exist.

Time as a material

The CDJ can change tempo naturally (affecting pitch like a record player) or independently (tempo without pitch shift). This isn’t just a feature — it’s treating time as a malleable material.

1, 2, 3, 4

Plus it can count! It counts BPM automatically. It identifies bars and beats. Listening to the mechanism, you realise it’s reading portions of the track into memory — functioning as a constant sampler. This allows instant, seamless loops: 1 bar, 4 bars, 8 bars. You can adjust in/out points and save them for recall later.

The machine understands musical structure, and gives you the tools to manipulate it.

Push the button

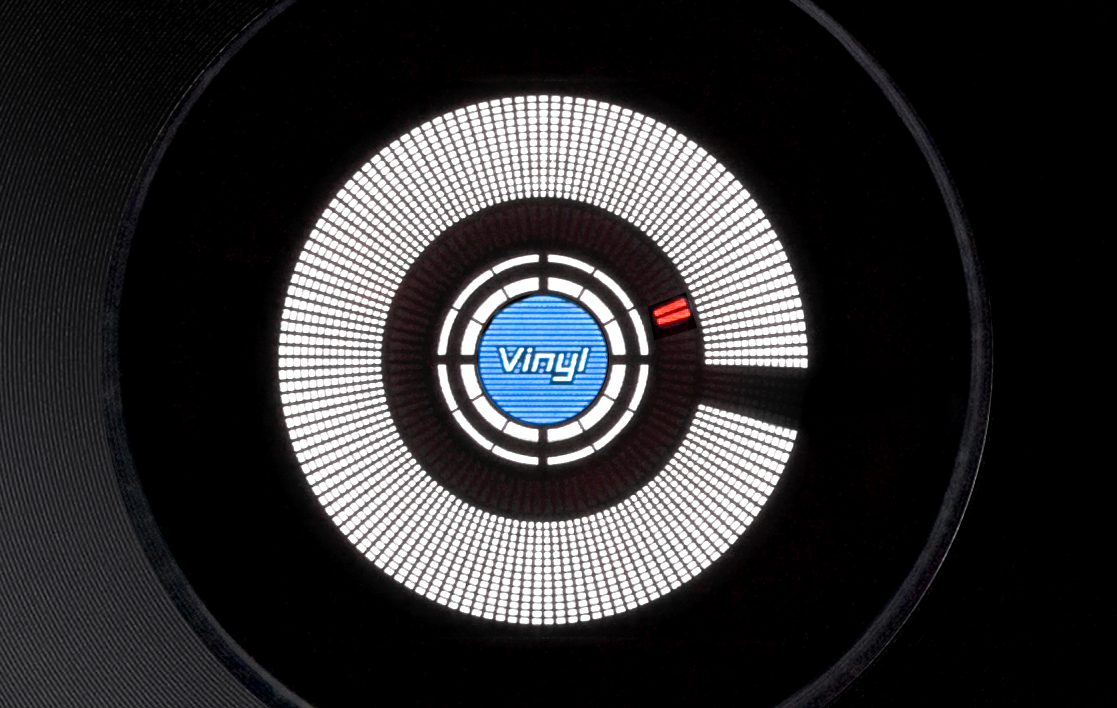

Like the first iPod, it has a physically moving jog wheel. But this is more sophisticated: the platter is touch-sensitive and pressure-responsive, with a circular screen in the middle.

A dial controls its behavior—simulating vinyl with gradual stops and starts, or tight digital response, or anywhere between. Thoughtful detail that matters.

The spinning needle

The circular screen is curious. Fixed LEDs provide visual spinning feedback for a virtual playhead on the record. Yes, it’s the inverse of a needle on vinyl, but it makes sense. It helps orientate the playhead when scratching.

You can scratch like vinyl, and this model has functions to let you experiment but return to the beat in time (called Slip). There’s a USB port, a chunky screen, and a dial for file browsing. Lots of buttons, mostly single function. No touchscreen (which is good). It’s built like a tank.

The connected instrument

Digital out for my DAC and active speakers. USB slot on top for a stick. But also: USB audio in — it can work as a sound card from your laptop. And ethernet.

Why does a CD player need ethernet?

That’s where things started to get interesting.